Interdependence, solidarity, cooperation

Since the 1980s, a number of converging factors have together contributed to giving the maritime a whole new meaning for the region. The collective responsibilities imposed across the whole region by international law (Montego Bay Convention) and the various multinational and transnational stakes involved; now militate strongly in favour of a concerted global approach to these issues... but implementation has run up against clear difficulties.

1. Cooperation: a necessity difficult to bring about

1.1. An evident interdependence

The opportunities and the need for cooperation between coastal states and territories are manifold in multiple domains involving the maritime: the region would clearly benefit from an effective and coherent network of shipping routes (passenger and cargo), a global policy for both medium and long-term conservation of marine resources, as well as measures for the prevention and control of all sources of pollution. All countries are also involved to varying degrees, in the prediction and prevention of natural hazards linked to the sea (integrated warning systems, shared means of response), in the laying of fibre optic, broadband communication cables, oil and gas pipelines, in the fight against cross-border trafficking (illegal migrants, smuggled goods, arms, drugs) across this whole maritime space, as well as against piracy which, whilst not reaching levels found in the Indian Ocean, remain a pre-occupation along the coasts of Colombia, Venezuela and South Haiti.

In other words, here are to be found a number of problems, which require monitoring, and demand at least some coordination, if not collaboration, between the countries of the region, given the large number of small, overlapping national maritime zones. But the obstacles are many.

1.2. Numerous checks

The first and foremost goes far beyond the sphere of just maritime affairs: it stems from the region's colonial history, whose lasting legacy has been the political fragmentation of the region into divided entities, one from the other, each with quasi exclusive links to their respective European metropoles, thereby leaving no historical tradition of collaboration in the area, indeed quite the contrary. The diversity of present-day regimes and political organisation (independent states, associated territories), the multiplicity of cultures, languages, legal systems, the weight of customary traditions, the wide disparities in terms of power, territory, demography and economy, the scant means of many states, hardly helps, facilitate the establishment of a sense of equality and solidarity.

More specifically, the varying responses to maritime issues by different states and territories remain a real obstacle to the development of integrated policies in this domain. The degree to which there is any identification with the sea, even the latter's importance in the everyday, such attitudes towards the maritime are hardly likely to be the same in small islands, washed by surrounding seas that constitute the never-changing horizon, as opposed to the large islands where those same waters appear less haunting, less omnipresent. Further removed are the isthmic and mainland states where their centres of demographic and economic activity are not solely Caribbean, but whose geopolitical and geostrategic ambitions, their spheres of interest, stretch across several regions (Pacific Ocean, continental neighbours...).

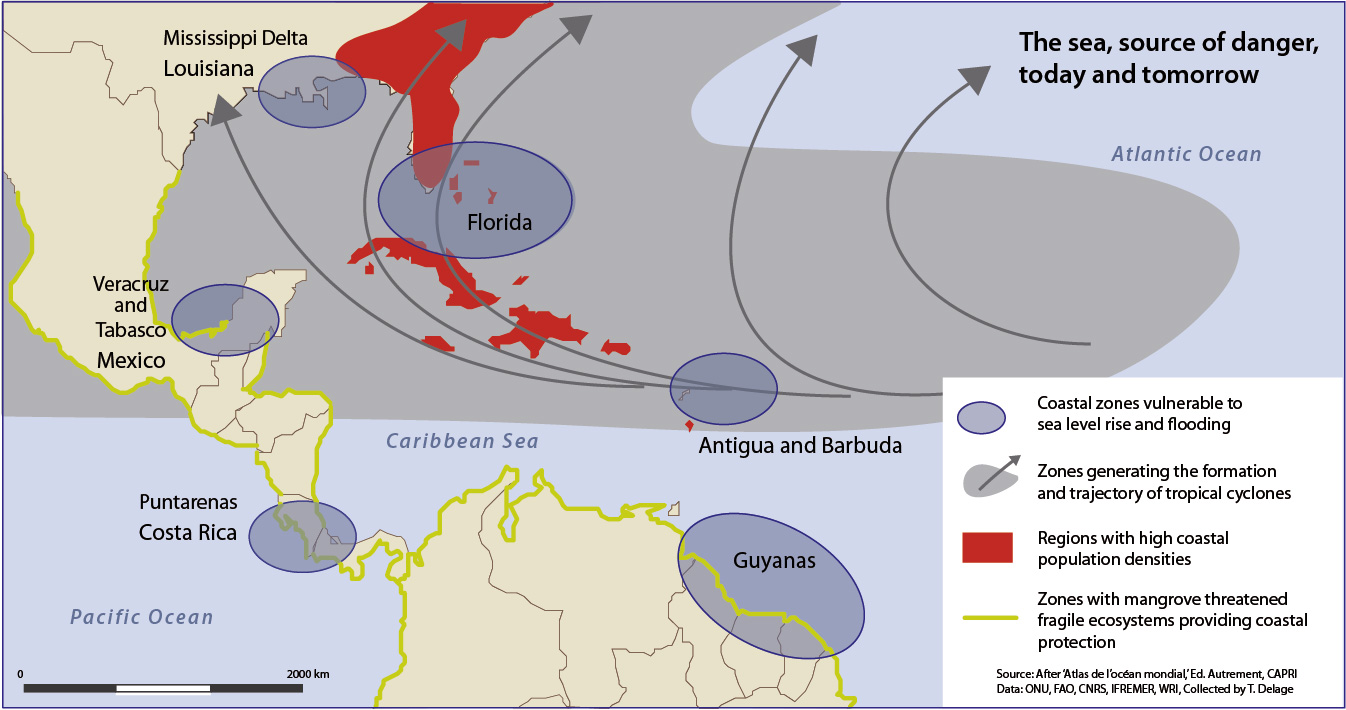

Divergent regional responses with regard to particular problems, the unequal degrees of exposure to risk, lie at the root of an absence of consensus to promote joint solutions. This is well illustrated in the case of rising sea level: small islands, together with a few, low-lying coastal territories (Guyanas) act as a bloc within AOSIS1 in unison with their counterparts in the Pacific and Indian Oceans (but not with their regional neighbours). They seek to make their collective voice heard at a world scale in order to strengthen their campaign against global warming. For all concerned the stakes are high, as the majority of their populations are concentrated in low-lying coastal areas. For those just above sea level, for example the Bahamas or Barbuda, it has even become a question of survival. Everywhere, sea level rise can provoke, often at short notice, the sudden exodus of “climate refugees”... yet these threatened zones still have difficulties in galvanising the support of continental mainland territories where the population is largely concentrated well away from the coast, and which remains less concerned.

A third obstacle stems from rivalry and competition between states, seen in the case of tourism where each seeks to attract cruise operators to their exclusive advantage. Accordingly, in the development of maritime links and port infrastructure, national interests as well as those of the transport companies, outweigh a more global view of the region taken as a whole.

The lack of disposable means for investment also constitutes a major impediment. Most states have only weakly development financial, technical, human, military resources, and are hardly in a position to promote ambitious projects, or even to ensure compliance with any edits or obligations agreed locally. One does not have to look far to explain the inadequacy of many policies involving regional cooperation. In many cases, the region has to rely on networks, on equipment, on initiatives, which are extra-regional. Forecasting cyclones is within the remit of world organisations or the United States. Maritime transports routes are decided by the main global hubs, and the chosen circuits of cruise liners obey the logic of companies whose headquarters are outside the region, and who take little account of those regional interests and needs.

Matters become even more complicated when the respective interests of one or other of the parties do not coincide. In the fight against drug trafficking using sea transport, the United States does not enjoy unanimous support within the region. For certain states, allowing the pursuit of traffickers by foreign warships in their territorial waters, is tantamount to renouncing part of their own sovereignty... without even speaking of the considerable financial stakes linked to the drug industry, whose to the highest political levels. The same differences of attitude are found regarding the protection of whales and dolphins (see below).

As such, the establishment of common maritime policies is neither self-evident nor easy to realise. Equally some areas of intervention are more easily adopted then others.

2. Environment: a test area for regional policy

2.1. A fragile and dangerous milieu

With few exceptions, the shores of the Caribbean Sea, more open to the wider ocean than its Eurafrican Mediterranean counterpart, are not characterised either by high population densities or by major industrial development (except very intermittently). However, given the scant size of most territories that border the sea, as well as their often-insular character, they do represent vulnerable and ecologically sensitive environments. The economic importance of the sea (tourism being the region's foremost activity), its “standard-bearer” image, and relatively consensual position with regard to environmental preoccupations also combines to strengthen their resonance. The latter consciously favours an imperative obligation to safeguard the sea, the mangroves, the coastline, the coral reefs, and their biodiversity for the interest and amenity of the region's inhabitants.2

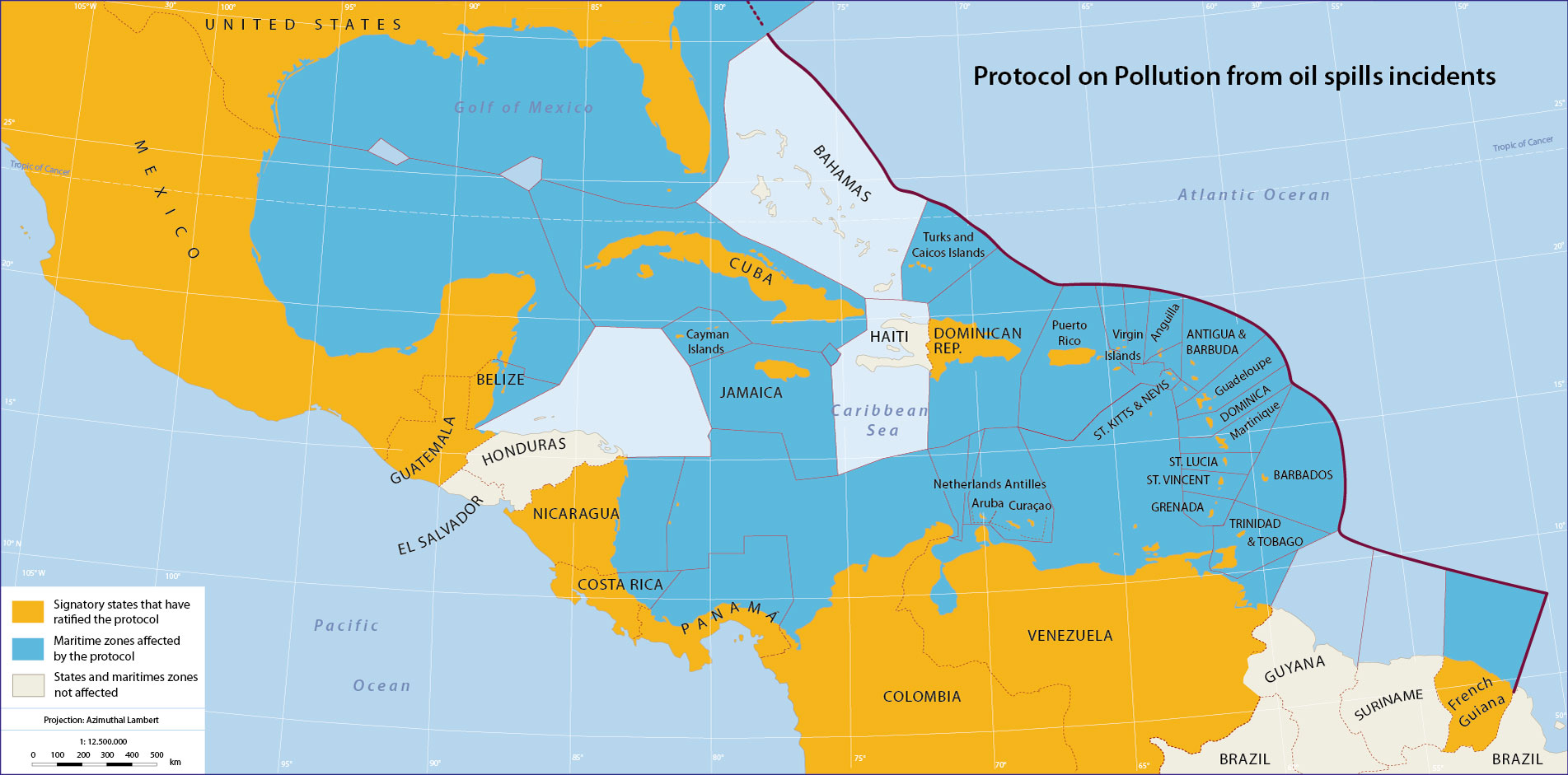

Firstly, the sea is threatened by diverse pollutions of marine origin: 1 500 fishing boats are ever present, in addition to 60 000 cargo vessels plying their trade each year, generating more than 80 000 tons of waste. The huge traffic of oil tankers destined for the giant refineries of Texas, Louisiana or the east coast of the United States, highlights in turn the risk of accidents or of dumping oil residue; to which should be added those linked to offshore exploitation of hydrocarbons, as much in Mexico as the United States and Venezuela (the Maracaibo Lagoon). Dangerous cargoes transiting the region also give rise to the threat of an accident or act of terrorism, for example, the Japanese nuclear waste being transhipped via the Panama Canal to France (the treatment centre at La Hague), as well as the reverse movement of re-cycled waste.

Coastal and maritime zones are also subject to risks linked to human settlement and activities, even those further removed from the coast: dumping of unfiltered or partially unfiltered water, of heavy metals (lead, copper...), illegal discharges of all types of other waste into open coastal waterways and drainage channels, as well as phyto-sanitary products used in agriculture. As a result, the Mississippi Delta and increasingly extensive surrounding areas of the Gulf of Mexico (around 25 000 km2 in total) are now categorized as part of the so-called “dead zone.”

The “dead zone” of the Mississippi Delta

The phenomenon of the “dead zone” results from an excess of nitrates and phosphorous in the Mississippi River. The latter stimulates the proliferation of algae which decomposes when dead, covering over the seabed. This decomposition absorbs all the available oxygen, preventing the presence of all other living matter. The phenomenon has been triggered by the increase in surface cultivation of maize for fuel energy production (more than 35 million hectares). The infatuation of the United States for agro-motor fuels has thus contributed to an increase in use of chemical fertilizers containing nitrates and phosphorous... According to some experts, this “dead zone” phenomenon will certainly exacerbate in the future by climate change, the increase in water temperature accelerating the decomposition of the algae and the redistribution of rainfall, modifying river flow rates.

Equally dangerous is the massive discharge into the sea earth particles: the deposition of mud over the seabed stifles growth of coral formations, and the turbidity of the waters leads to the disappearance through lack of light of all aquatic life. Deforestation and urbanisation, in accelerating both stream turn-off and erosion, serve to exacerbate the situation. It is not by chance that the problem assume such formidable dimensions in Haiti, but very few are the number of countries spared, and in Martinique, for example, the waterborne alluvium of the Lézarde, Rivière-Salée together with a few other water courses, are contributing to the rapid silting-up of the upper reaches of the bay of Fort-de-France.

The coastal areas of the Caribbean are suffering from worrying levels of environmental damage, the result of degradation originating from both natural and human causes. The erosion of beaches has become a region-wide problem. Everywhere, they are in retreat, sometimes by several metres per annum (4 m on average in Barbuda, 1 to 3 m in Dominica). The phenomenon is brutally accelerated during the onset of cyclones and heavy sea surges. In 1995, the beach of Coco Point (Barbuda) retreated by 25 m in half a day, following the passage of Hurricane Luis; in Grenada, the most frequented tourist beaches were destroyed by Hurricane Lenny in 1999, with serious economic consequences (Desse M. and Saffache P., 2005). In Dominica, many sandy inlets were drastically affected by cyclone damage where previously there had been excessive removal of materials for the construction industry.

The worrying symptoms of the impact on ecosystems are multiplying: diverse marine species threatened by pollution or the destruction of their habitat, are in the process of disappearing, as in the case of the monk seal or the Caribbean Manatee (“sea cow”) of which only a few dispersed specimens remain. All species of turtle remain threatened by hunting, poaching, trawling, and ‘phantom fishing'.3 Other animal and vegetable species are exploited without any real control, and are becoming increasingly rare: corals, shellfish, crustaceans, sea-fish and mammals (and everywhere the mangroves are in retreat). In Guyana, over-exploitation is clearly in evidence: in just a decade, caught red snapper has decreased in size by more than 10 cm, their average weight from 2 kg to 800 g, and the age at capture is now less than that of first maturity. The case of the Queen conch (Strombus gigas) is also symptomatic of the same trend.

CITES suspends commercial exploitation of the Queen Conch

Found across the whole of the Caribbean, from Florida to the northern east of South America, the Queen Conch lives in the waters of 36 countries and dependent territories, i.e. nearly all its member states. As a species, it shows a preference for sandy sea floors at shallow depths, but can be found at 100 m below the surface.

Since the 1990s numerous worrying indicators have led to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of wild fauna and flora (CITES) intervening to protect this resource. It thereby envisages a series of forceful measures to regulate fishing and to re-establish this species. Since 1992, a CITES permit has become a statutory requirement for all exports.

Following these CITES rulings, two of the main states within the ‘Queen Conch' catchment zone (Dominican Republic and Honduras) have accepted not to authorise further export of this species as of 29 September 2003. Haiti, however, did not follow suit, and CITES accordingly imposed a boycott on Haitian ‘Queen Conch.'

Two causes converge to explain the present situation. For several decades, the fishing of the ‘Queen Conch' has changed in scale and assumed a commercial level of production commensurate with both local tourist and international markets. It has become one of the most important fishing resources of the Caribbean, generating both a significant turnover and numbers employed. What followed, however, was a degradation of the species habitat, in particular the large-scale loss of fishing grounds in shallow waters, near to the coast. Faced with this rapid collapse in available stocks, it was necessary to close down, either totally or temporal the fishing of this species in a number of countries: Dutch West Indies, Colombia, Cuba, Florida, US Virgin Islands, Mexico, Venezuela. The situation today remains very fragile.

Source: http://www.mediaterre.org/caraibes/, 2009

Notwithstanding the various it faces, the sea itself can also be a source of danger: it generates and provides a vehicle for hurricanes and their associated phenomena (cyclonic sea surges). The tsunamis, certainly rare and of normally limited amplitude, are viewed as potentially less dangerous, at least as represented in the collective memory (the last destructive catastrophes date back to 1882 for the San Blas isles near Panama, 1918 for Puerto Rico and 1946 for the Dominican Republic). However, the region (albeit with an unequal impact) is more concerned by sea level rise.

2.2. A veritable arsenal of judicial and institutional measures

Since the 1980s, the region has built up a powerful panoply of judicial and institutional measures aimed at conserving and valorising the marine environment. In 1983, a ‘Regional Agreement for the Protection of the Marine Environment,' also known as the “Cartagena Convention,” was signed within the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). It was the first of its type in the world, complemented by three special protocols (annexe a). These highly detailed and ambitions ‘frameworks' are the only ones solely concerned with the whole maritime domain of the Caribbean.

The ‘Cartagena Convention' has facilitated international cooperation, for example within the RAMSAR4 programmes on the protection of wetlands, or again with the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI). Countries of the Caribbean are also signed-up members of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS), of the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes, and of the Convention on Biological Diversity. All these conventions advocate and initiate cooperation over a highly diversified domain, which promotes everything from research to data collection, the involvement of civil society, and the putting in place of measures of evaluation and protection.

In December 2001, under the aegis of the ACS (Association of Caribbean States), a Convention on Sustainable Tourism Zone of the Caribbean (STZC) was signed. Whilst no specifically “maritime,” a large part relates to the sea and its coastal areas, viewed as an integral whole. Here again, the objective is to favour “a tourist development which remains sensitive to the preservation of a socio-economic and environmental balance.” A major feature of the project resides in the will to promote an integrated regional approach to tourism: the development of a Caribbean ‘brand' of sustainable tourism, a project to ‘package' multi-destination tourism, as a total break from the “each for itself” approach which still prevails today. Examples would include Guadeloupe-Dominica or Trinidad-Venezuela.

Good intentions exist and the tools are available... but what specific progress has there been to date?

2.3. Undeniable progress

The major international accords have played a positive role in persuading governments within the region to protect the environment. The number of protected maritime spaces has multiplied, today totalling more than 300 (80% of which are less than 20 years old) across all states, even the smallest and poorest.

The US Virgin Islands Model

This archipelago has long viewed the maritime milieu as its principal economic ‘trump' card, playing a precursor role within the region. Developed with determination over a long period, a global policy aims to ensure water purity, clean seabed, the integrity of the coral reefs and the richness of life forms sheltered there. Underwater hunting is banned, waste discharge from ships severely limited, mooring of pleasure craft regulated so as to avoid destruction of coral formations by chains and anchors. Moreover, and crucially, effective control measures have been put in place.

Regional, sub-regional an bi-lateral initiatives abound. Saint Lucia has benefitted from Barbados' expertise on coastal protection. Conservation programmes regarding sea-turtles have been launched (with 11 states participating), as well as for the Caribbean ‘sea-cow' (Trichechus manatus), the largest ‘Sirenia' still in existence (5 participant states). A regional anti-tsunamis alert network is being set-up, and should be operational in the near future, and integrated within the global system. Far from being negligible, such realisations are witness to rapid progress in a newfound recognition of marine ecological sensibility across the region.

2.4. ... But much still remains to be done

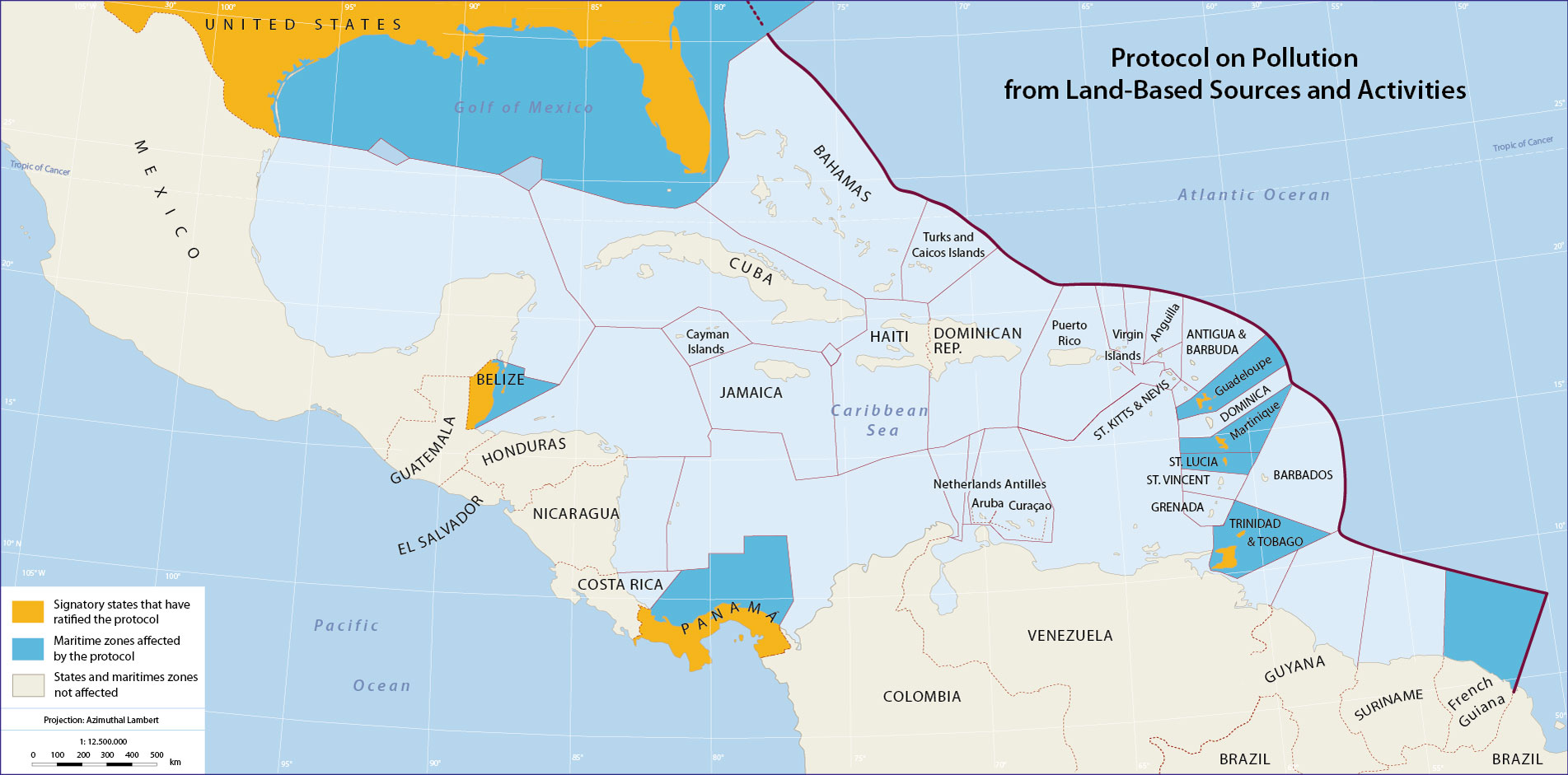

An important gap still exists between statements of principle, the will to act, and their actual realisation. A number of states have yet to sign and ratify the Cartagena Convention5 and its protocols (annexes b-c-d). Note also that the number varies greatly from case to case. The effective launch of the STZC has proved rather slow. Should one read here a lack of commitment in some countries to what they consider non-priority problems? Or is it rather a wish not to “tie one hands” by acceding to constraining instruments possibly affecting national interests? Reasons vary, but these non-ratifications, particularly by large states, clearly undermine the impact of these conventions.

Only 30% of marine spaces theoretically subject to protection are properly managed, the pace of their listing by far outweighing the putting into place of the corresponding means. In the domain of fishing everything still remains to be done as regards the harmonization of regulations (mesh size of nets, proscribed fishing periods...) or again, the establishment of quotas for over-exploited migratory species. Neither is there an agreed common position concerning whale hunting.

A whale sanctuary in the Caribbean?

During a meeting of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) in St. Kitts (May 2006), France announced the creation of a sanctuary for this species in the EEZ of the French Antilles.6 In order to have any real meaning, this initiative needed geographically to cover a sufficiently large zone, necessitating the full participation of neighbouring states. The latter could not be assumed as amongst them several had traditionally hunted whales (albeit on a modest scale) which gave them membership of the IWC, but more particularly because Japan, the main supporter of an end to the moratorium on whale hunting, had attracted public notoriety over strong pressures exerted on certain small states, by linking their development aid to votes...

The balance sheet thus appears mitigated, with progress in many areas stalled... The central place unanimously accorded to the sea today was barely in evidence just a few decades ago. Up until the 1980s, the sea remained a marginal space, as much in its representation as in the preoccupations of those post-colonial societies which remained above all land and agriculture-based (even in the islands), which considered themselves little affected by the stakes in question. In recent decades, a profound mental transformation has come about slowly and unequally, but finally quite rapidly, a spectacular turnaround in the way coastal peoples of the Caribbean apprehend “their” sea, and their relationships with it.

Over-riding factors of disunity and of physical, cultural, economic, and other cross-regional divisions, the sea has progressively assumed its place in the collective imagination as the smallest common denominator tying together the diverse countries and territories of the region. In short, it represents “the common heritage of the peoples of the Caribbean,” a regional stake that engages everyone, acting as a handy and undeniable anchor of regional identity. Economic stakes and political vision in turn are brought together. Regional policies linked to the sea provide opportunities to represent more clearly and tangibly the collection destiny of the “Caribbean Community.”

At the culmination at what appeared as an unpromising start, the progress achieved over recent decades seems remarkable but cannot conceal the persistence of a number of gaps and failures. A real awareness of the issues appears much more evident in the islands, especially the smallest, than in the mainland states where national interests often take precedence over regional solidarities. Convincing arguments still need to be pursued forcefully to ensure the full acceptance of the federating role that the sea provides as the “regional cement,” the engine of a new dynamic in regional development, that is her legitimate inheritance.

Annexes: The Cartagena Convention and its protocols

a) The main dispositions of the Cargagena Convention

The Convention for the protection and development of the marine environment in the Caribbean region (Wider Caribbean Region - WCR), the so-called Cartagena Convention was signed on 24 March 1983. It is the only treaty with an environmental agenda, which embraces the whole region. It covers 23 states out of a potential total of 28. It includes 3 specific protocols relating to pollution by hydrocarbons (to which the region is particularly exposed, see above), pollution linked to terrestrial activities, and the protection of wildlife.

These detailed and ambitions texts, or “frameworks,” are the only ones, which specifically cover the whole of the Caribbean maritime domain. They were ratified by France on 13 November 1985, and became binding after the 9th ratification on 11 October 1986. The Secretariat in Kingston, Jamaica, operates under the auspices of the UNEP, created in 1986.

The signatories evoke “the social and economic value of the marine environment, and the duty to protect it.” Included for protection are the special hydrographic and ecological characteristics of the region, and its vulnerability to pollution. It deplores the present situation by “the absence of sufficient integration of an environmental dimension into the development process,” and defines the main objectives to be achieved, namely “the protection of the ecosystems of the marine environment.” It considers as indispensable “the co-operation amongst signatories themselves and with competent international organizations,” and lists proposals for the operational actions required at both national and regional levels.

This Convention is part of a global protection plan for me marine environment (UNEP: United Nations Environment Programme). It constitutes a legally binding engagement on the part of its members, both individually and jointly, to protect, develop, and manage their coastal and marine resources (species, sea spaces, ecosystems). It also has the particularity of equally taking into account the associated terrestrial zones, including the adjacent drainage basins and to monitor as much their protection as their development. In many ways, it represents the precursor of what the international community would subsequently enact at a global scale. Above all, the Convention demands the protection of rare and threatened species, insisting on the creation of specially protected zones. In contrast to worldwide environmental convention, the regional conventions exhibit a transversal dimension covering a large range of subject areas from problems of pollution to those of the conservation of species and marine ecosystems.

One already important action has been under taken and agreed in the context of the SPAW Protocol of 1990, concerning Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife, signed in 1990, with offers support to governments in different fields:

• Constitution of a database of 300 protected marine zones in collaboration with the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park of Biscayne and the NGOs. It facilitates the exchange of information and collaboration between managers of different zones in order to better respond to problems that might arise;

• Inventory of species to be protected (marine and coastal flora and fauna);

• Establishment of the Regional Centre of Guadeloupe;

• Publication of a guide for the management of protected zones and related organisations in search of funding;

• Organisation of training seminars for managers on the problems relating to protected zones;

• Establishment of a conservation programme for sea turtles across 11 states, and for the West Indian Mantee (‘sea wolf”: “Trichechus manatus”) in 5 states;

• Surveillance, management, and conservation of coral ecosystems in liaison with ICRI (International Coral Reef Initiative) as well as ICRAN (International Coral Reef Action Network);

• Promotion of good practice in the management and development of sustainable tourism in coastal zones.

The signatories of the Special Protocols of Cartagena Convention

b) SPAW Protocol: Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife

c) LBS Protocol: Pollution from Land-Based Sources and Activities

d) Oil Spills Protocol: Pollution from oil spills incidents

1 AOSIS (Alliance of Small Islands States and low-lying coastal states): Coalition of states particularly vulnerable to sea-level rise, who share a common position on climate change and the long-term correcting measures required. Bringing together 43 states and observers from all regions of the world, played a key role in the elaboration of the Kyoto protocol.

2 Cartagena Convention of the Indies, 24 March 1983, echoing the spirit of the recommendations of the Montego Bay Convention of 1982.

3 Description applied to fishing which continues to leave in situ nets, either lost or abandoned, trapping for months or even years both fish and sea mammals, as well as sea birds.

4 Launched at Ramsar, Iran, in 1971.

5 States not having signed or ratified: Bahamas, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, St. Kitts and Nevis, Suriname.

6 Following those established in Polynesia, New Caledonia and the Mediterranean.

top

|

|