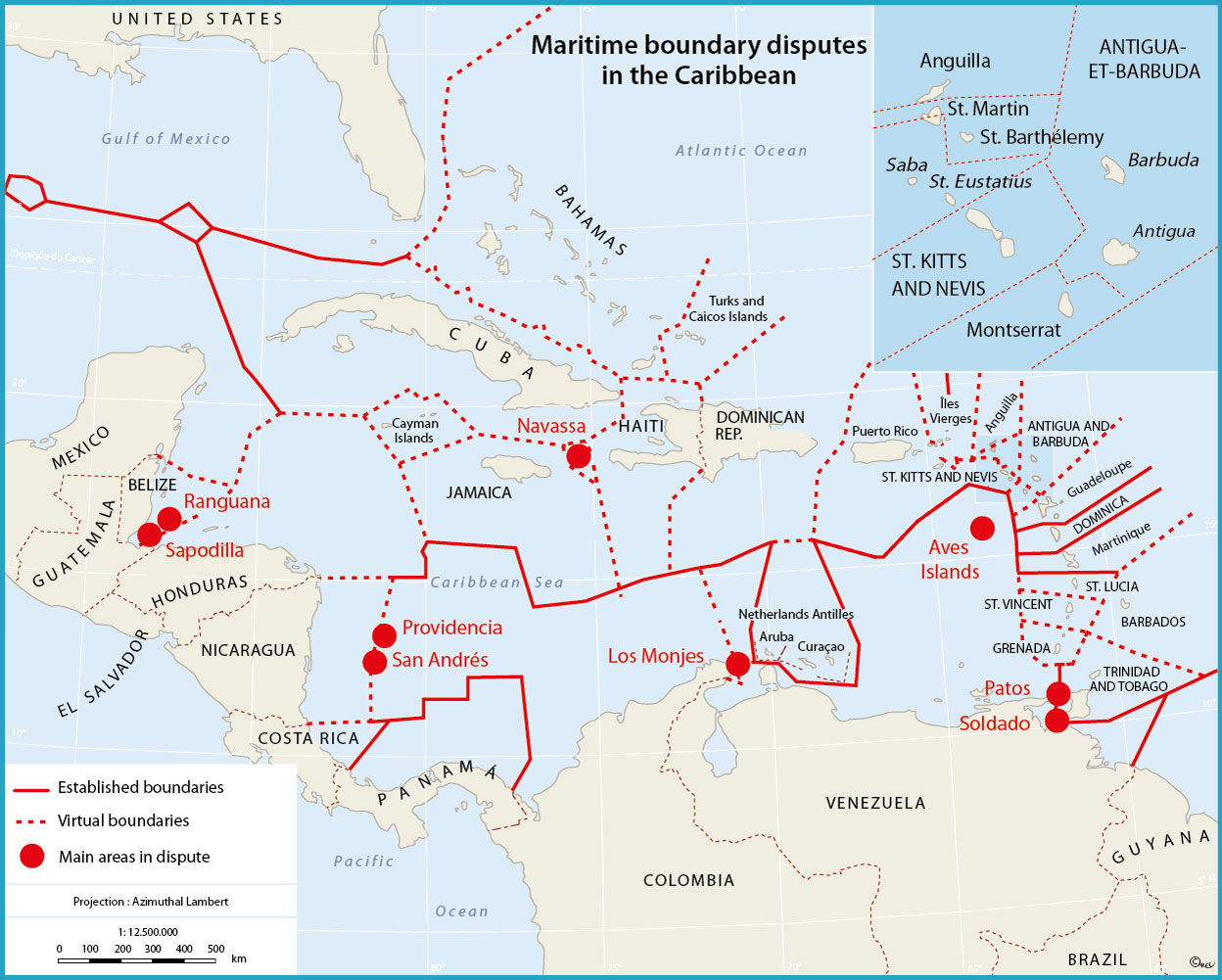

Two thirds of the Caribbean's international maritime boundaries have yet to be the object of an agreed convention between the bordering states in question. Problems, disputes, demands linked to the sea are numerous (see “L'espace des Caraïbes structure et enjeux économiques au début des années 2000”, annex 2, cahiers Antilles-Guyane) and by nature, somewhat varied, some long established and historic, others of more recent date relating to the rulings of Montego Bay Convention.

1. ‘Historic' cases of litigation

For good reason (being the only cases), these relate only to territorial waters. Generally, they emanate from land boundary disputes and as such only concern the mainland territories, and in particular, those of the isthmus where inter-state relations have remained poisoned for nearly two centuries. Such is the case of the long-running dispute between Guatemala and Belize.

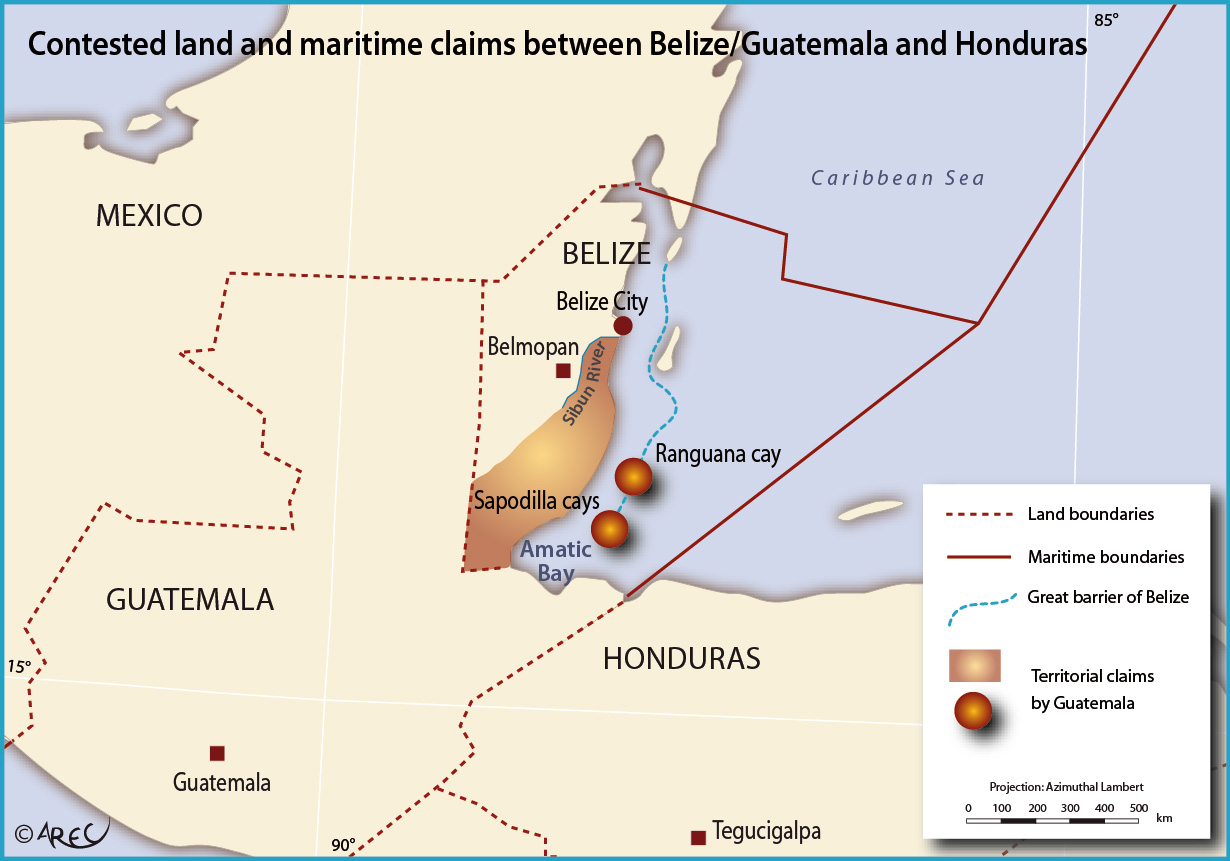

Maritime and mainland boundary disputes between Guatemala/Belize and Honduras

Guatemala disputes the 1855 Treaty with its neighbour and has re-activated its claims to half of the territory of Belize as far as the River Sibun, as well as to the reef areas (“cayes”) of Ranguana and Sapodilla (sandy islands on a Corallian sub-foundation, situated in the southern part of the Great Barrier of Belize), and as a consequence to part of the waters of the Gulf of Amatique and the Gulf of Honduras from which it is currently excluded.

Maritime and mainland boundary disputes between Venezuela and Guyana

Similarly, the claims by Venezuela over a large part of Guyana (as far as the River Essequibo) also include the corresponding maritime zone.

More recently, the virulence of these disputes has been exacerbated locally by the presence, whether proven or assumed, of mineral or sea-life resources, as it is along this narrow coastal band that traditional fishing, hydrocarbon deposits, tourism, as well as the potential for aquaculture and marithermic power generation, are concentrated.1 Differences between Colombia and Venezuela over the tiny islets of Los Monjes at the entrance to the Gulf of Venezuela would be less acrimonious but for the significant presence of fishing resources, as well as the probability of oil reserves in nearby ocean depths.

The Los Monjes Archipelago

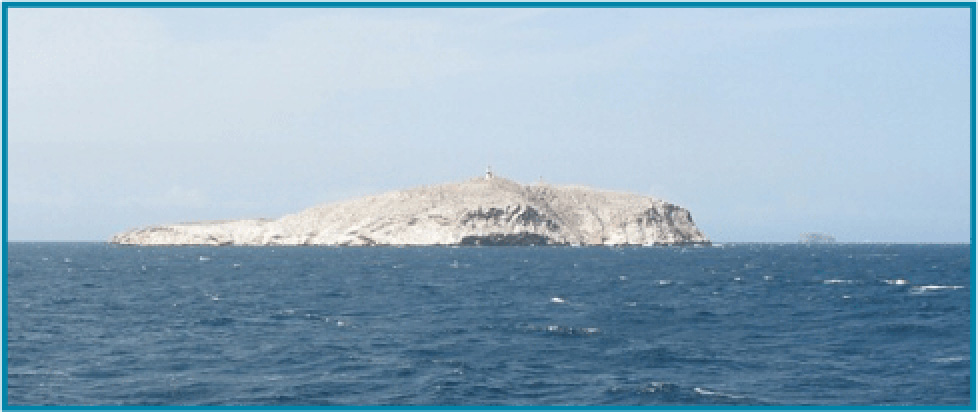

This Venezuelan archipelago, 0.2 km2 in area, is situated at the mouth of the Gulf of Venezuela, 35 km from the Guajira Peninsula (Colombia) and 45 km to the northeast of the state of Zulia (Venezuela). It is made up of three groups of uninhabited rocks and islets (except for a Venezuelan garrison) and without vegetation: South Monjes (70 m in altitude), East Monjes (43 m) and North Monjes (41 m).

In 1833 (Treaty of Michelena Pombo), Venezuela recognises Colombia's claim to the larger part of the Guajira Peninsula... but the Venezuelan Congress refuses to ratify it. In 1891, arbitration by the Spanish Queen, Maria Christina, recognises Colombia's right to the largest part of Guajira based on the decrees (‘cedulas') of 1777 and 1790 by which the region was divided. This position is further confirmed in 1922 as a result of Swiss arbitration. But it is only in 1952 that the Colombian President, Roberto Urdaneta Arbalaez recognises Venezuela's sovereignty over the Los Monjes Islands, where a Venezuela is now established. The problem however is not totally resolved: in 1987, the arrival of a Venezuelan frigate provokes a sudden mounting of tension and military mobilisation. More recently, Venezuela has constructed fishing installations in order to exploit the local resource base.

South Monjes

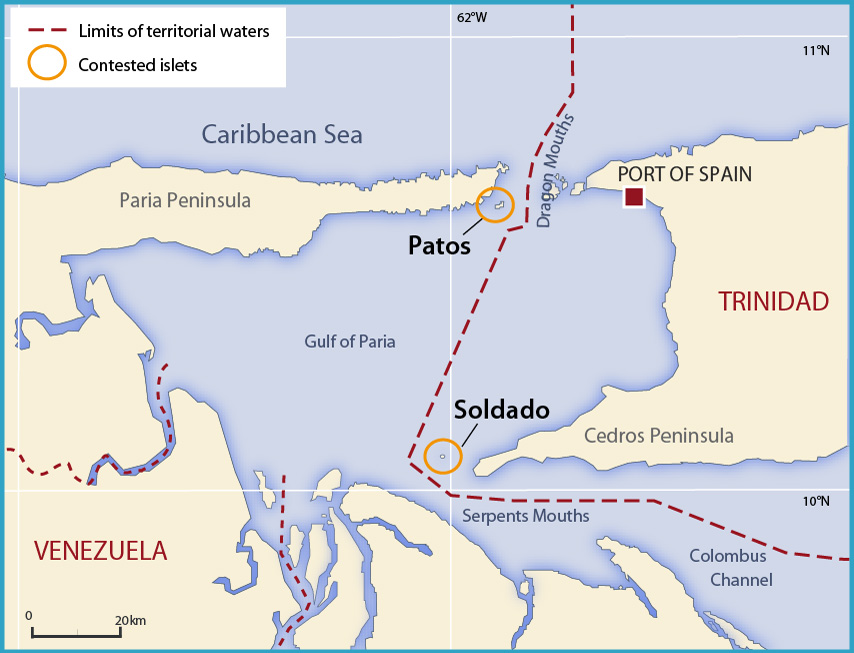

Litigation between Trinidad/Tobago and Venezuela is particularly complex.2 It dates back to the colonial period and continues after the independence of Trinidad and Tobago, taking on various dimensions, territorial (maritime boundaries), economic (fishing, hydrocarbons), all set in a general context of bad relations between the two states.

Maritime litigation between Trinidad/Tobago and Venezuela

The origins of this dispute stem from the ownership of two tiny rocks, Patos (50 hectares) and Soldado (0.4 hectare!), 8 km in the line of prolongation of the southwest point of Trinidad, some 11 km from Venezuela.

After C. Fleury: History of the territorialisation of maritime space around Trinidad (2002)

These conflicts whose roots plunge back into colonial history are those, which exhibit the most resilience. They gave rise in the not too distant past to numerous, and sometimes terrible wars, particularly in the isthmus. Resentments have proved long-lived, and the settling of some disputes is still in abeyance, but with neither side wishing to see degeneration into violent confrontation.

2. Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), sources of new contestation

The problems linked to EEZs are more recent date and concern most of the states and territories of the region, such as the islands, absent from the list of ‘historical' conflicts. They in turn tend to be less acute as they cover stretches of sea where claims of entitlement are not as rooted, and where resources are generally more limited. With some local exceptions, Caribbean maritime space is not rich in fish stocks. Nearly all countries are net importers of products of the sea, and only a few maintain deep-sea fishing fleets, with none appearing high up in world rankings with regard to fishing. Neither are the commonly exploited resources normally found on the sea floor currently in evidence in any quantities... although the inventory is far from complete. The known potential of EEZs is accordingly not sufficiently great as to warrant development in the foreseeable future, and for most of the countries in question to commit the means and effort as a matter of priority... for the moment the territorial sea suffices. In any case, they hardly have the means, whether technical, military, financial or just human, to exercise any real sovereignty over these huge expanses of sea, to control and eventually exploit them.

Most of the low key judicial battles that certain countries bring before the international courts, to establish their rights in law relate more to questions of prestige, national sensitivities and sometimes simply the desire to maintain a claim on potential resources for the future, rather than to pursue any short team economic stake. However, the discovery and impending exploitation of the major oil field of Hoyo de Dona within the Mexican, United States and Cuban EEZs may well shuffle the carts (see below). The two most spectacular disputes (covering hundreds of thousands of square kilometres involving numerous states) are by their nature easily comparable: these relate to the EEZs of Colombia and Venezuela (neither state having ratified the Montego Bay Convention) and which appear clearly on the map as “anomalies.”

Little cause, big effect: the tiny islet of Aves has been used to justify a hugely disproportionate extension of Venezuela's EEZ as far as the open sea adjoining Guadeloupe. This appropriation has been effected with the endorsements of France. Netherland and United States (in the name of their island dependencies within the zone).

Aves Island

The Isle of Aves (‘Isle of Birds') is a sandbank 375 m long, varying in width 15 to 50 m, with a maximum altitude of 3 metres, and resting on a corallian sub-foundation. Well away from all the busiest shipping lanes, and very isolated from other islands (200 km from Guadeloupe, 230 km from Dominica and 550 km from Venezuela of which it is a “federal dependency,”) and not even offering a secure mooring point. In 1980, the islet was submerged and divided in two by Hurricane Allen, but later re-united. As a place of rest and nesting for various species of marine birds and green turtles, there is no permanent habitation and very little vegetation. Discovered in 1584, it was subsequently claimed in turn by the Spanish, British, Portuguese and Dutch. From 1878 to 1912, it was exploited by the Americans for its guano until the resource was exhausted. Venezuela now maintains a small garrison of some twelve soldiers, a situation contested by several states.

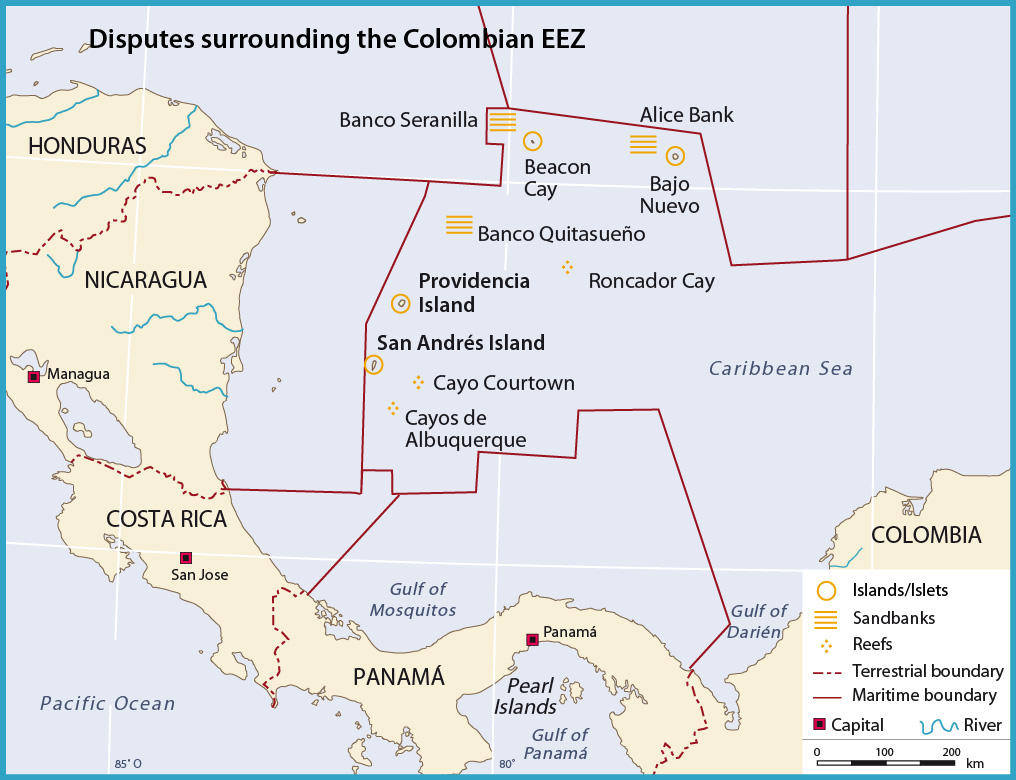

In the case of Colombia, control of the archipelago of San Andres and Providencia, located in open sea off the coast of Nicaragua, together with a few isolated and distant rocks and uninhabited sandbanks, allows Colombia to claim an immense EEZ, which pushes deep into the heart of the Caribbean Sea.

San Andres and Providencia

This Colombian archipelago of around 52 km2 with some 60 000 inhabitants is situated some 700 km from Colombia's northwest coast. It is made up of the two islands of San Andres and Providencia to which can be added numerous islets. The island of San Andres is administered by an elected governor. The official language is Spanish but many of the inhabitants speak an English-based Creole. For more than 200 years, this island was in dispute between the British, Dutch, French and Spanish before Spain's sovereignty was officially recognised by the British at the Treaty of Versailles. For a long period the islands hat served as a refuge for pirates like Manswelt or Henry Morgan. They are currently claimed by Nicaragua.

The Montego Bay Convention3 specifies, however, that in order to avoid violations “rocks that do not lend themselves to human habitation or proper economic livelihood may not lay claim to designation a either EEZ or continental shelf.” Such appropriations are generally contested by those countries whose own EEZs are correspondingly reduced (Nicaragua is demanding a quadrupling of its EEZ). They consider such extensions as unjust and illegitimate, seeing in such annexations a will to dominate.

The island of Navassa, off the southern point of Haiti poses a problem of the same order. Haiti contests its appropriation by the USA, which has occupied the island since 1857. This dispute has prevented the definitive delimitation of the maritime zones of neighbouring states (Jamaica, Cuba, Haiti).

Navassa

Navassa is an uninhabited islet situated 54 km from the southwest point of Haiti of which it had long been a dependency. Despite protest from Haiti, which continue to the present-day, the USA claimed the island in 1857 in order to exploit its guano, which lasted from 1865 to 1898. A 46 metre high lighthouse was built in 1917, which ceased to function in 1996. Administration of the island has been overseen successively by the American Coastguard Service (until 1996), then by the Department of the Interior. Finally in 1999, the island which is of exceptional interest regarding biodiversiy in the Caribbean became a national refuge for wildlife and placed under the authority of the Fish and Wildlife Service of the Department of the Interior, which oversees numerous scientific studies.

As for determining the limits of the Mexican and United States EEZs in the Caribbean, it reads like a novel.

The phantom island of Bermeja

The existence of the uninhabited Mexican island around 100 miles offshore from the Yucatan is repeatedly attested from 1864 to 1946 in several documents and publications.4 With a surface area of 80 square km (much more than a simple rock!), its coordinates (22° 33' N by 91° 22' W) are recorded with precision. Now in 1997, at the opening of negotiations between Mexico and the USA to fix the boundary line between their respective EEZs, a Mexican military naval expedition comes to the conclusion that the island has disappeared! The Clinton-Zedillo accords of 9 June 2000 thus do not take it into account. By a strange coincidence, it emerges that the boundary now adopted awards to the United States the major part of the enormous oilfield of Hoya de Dona, estimated at 22 billion barrels (which if Bermeja had existed would have gone to Mexico).

Since this episode, several troubling facts have served to re-launch the polemic surrounding the whole affair in Mexico: the promotion to admiral by President Zedillo, signatory to the accord, of the head of the expedition in 1997; the returns on business dealings (in the United States!) of the same President; the suspect death of a senator who accuses the authorities in power at the time of corruption and of having sold out Mexico's wealth to American multinationals.

The mystery of the “Phantom Isle” remains unfathomable: did it ever exist? (It seems there neither any maps or photos). The most extravagant hypotheses have been publicly aired by the many different voices of the parliamentary left-wing opposition, and relayed by the press. Had the island been submerged by sea level rise brought about by global warming? (But the only area of seabed that might correspond to the location is at a depth of -40 to -50 metres!)… Or was it simply dynamited by the CIA? Without doubt, a story to follow...

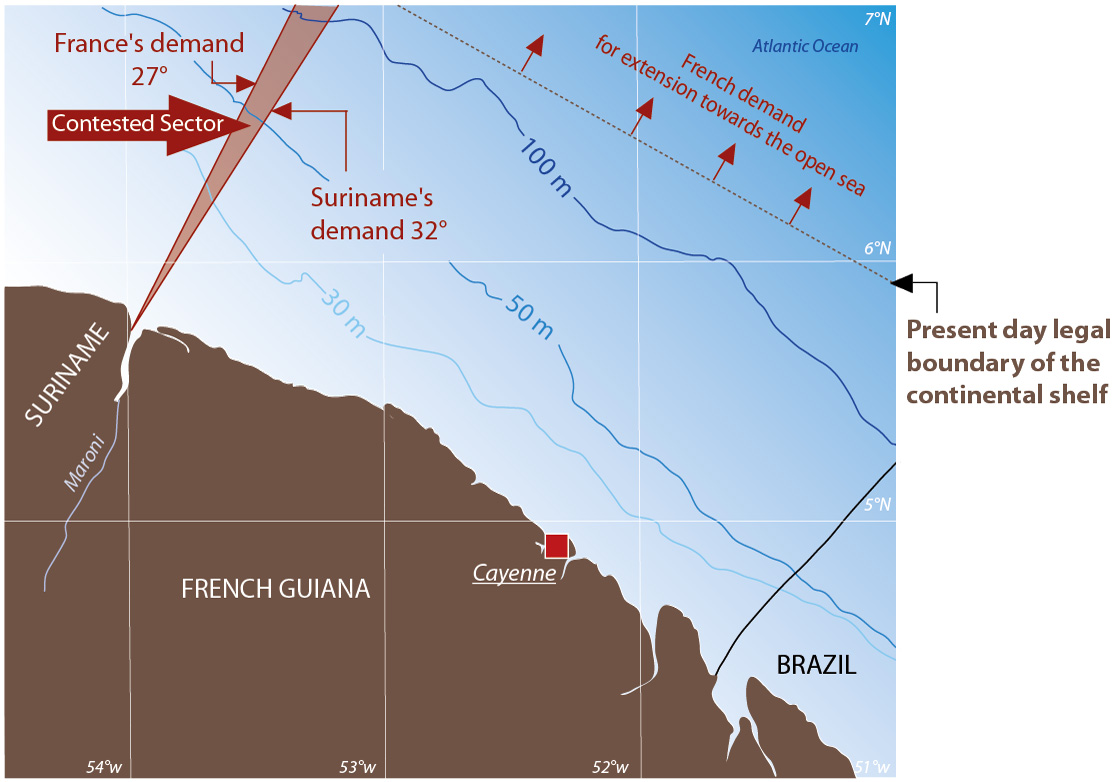

3. The continental shelf, a future stake

Another type of demand recently, hither to rare in the region, relates to the limits of the continental shelf. It does not impact directly on boundaries between states but those in contact with international waters, the high seas. In May 2007, France submitted to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) a request for an extension of its continental shelf. France seeks to exploit probable natural resources yet to be extracted, such as hydrocarbons (a programme of seismic prospection has identified potential oil reserves of over 500 million barrels) as well as natural gas, mineral resources and marine biotechnology. The stakes are important: after Mai 2009, the sea beds left unclaimed will be considered as world heritage sites of humanity, and thereby untouchable. This in turn demanded preliminary resolution of the limits of territorial waters and of the EEZ with Suriname. The negotiations have yet to be concluded (see map below).

4. Fishing disputes

Thus far, the motivation behind disputes and tensions all stem from the fixing of the maritime boundary limits. It is also because the limits are not being respected: the pulling over of vessels fishing illegally in ‘foreign waters' from time to time hits the headlines in the press. Examples abound, not least because the new maritime boundaries upset well-established traditions. Thus, the fishermen from northern Martinique have frequented for decades a “sek” (upper deep) at 100 metres below the surface, with plentiful fish stocks, some 40 km to the northeast of the island, known as the Diên Biên Phu banks.5 This bank now finds itself cut in two by the international maritime boundary, and shared with Dominica. Fort the Martinique fishermen, this is difficult to accept, much better equipped than their Dominican counterparts, and who traditionally accounted for most of the fish. Their repeated infringements (whether deliberate or accidental) of the boundary have given rise to several serious incidents. The same applies offshore from Saint Vincent.

Why the Madico Karine should not have been fishing there

The sea fishermen of the ‘Madico Karine,' a Martinique registered vessel pulled over on 18 May 1998, by the St. Vincent authorities, were in the wrong. They should not have been fishing in the EEZ of Saint Vincent. “In law, they have no excuse,” the view of Loïc Laisné, the Director of Maritime Affairs, against which there can be no appeal. Saint Vincent has every right to assert the legal status of its EEZ and France can hardly contest the 150 000 franc fine payable by the Servipech Company in order to retrieve its boat.In effect, the division of the Caribbean Sea and its resources, between the various states is, to say the least, complex. The Montego Bay Convention did not abrogate ancient customary rights for those countries that did not sign. Elsewhere, bit-lateral accords regarding boundary limits have been separately signed by France and Venezuela, Dominica and Saint Lucia. But the ‘Madico Jeanne' episode, the Martinique vessel arrested last month by the Barbados authorities, has served as a reminder that Barbados, Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent still dispute the whole basis of the delimitation.Besides, states can if they so wish, sign fishing accords amongst themselves, and private accords can exist between a fishing company and a state which then awards the necessary licence. In other words, within the Caribbean there are accords that are best described as tacit agreements: these accept that traditional fishing may encroach on other EEZs to pursue migratory species – tuna, bream, dolphin, marlin, Spanish mackerel... – but these non-written concessions can be revoked at any time.

Extract from France-Antilles, 31 May – 1 June 1998

Behind all these episodes lie the susceptibilities of the poorer small states confronted by the ‘arrogance' and the infringements of the more secure states. For a time in Venezuela waters, matters took on a more serious turn: the increasingly violent boardings of Trinidadian fishing vessels, by the Venezuelan Guardia Civil resulted in both deaths and injuries. Without dwelling on unexplained disappearances in a zone characterised by heavy shipping traffic of all types, a climate of violence and insecurity had developed. Finally, in Guyana waters, the interceptions of Korean trawlers or of the Brazilian “tapouilles” fishing illegally became a common occurrence, some ending in veritable armed confrontations.

As such, the application of the new ‘Law of the Sea' in the region produced a dual paradox: firstly, the desire to protect the smaller poor countries has instead somehow favoured the larger ones, while secondly the drive to resolve conflicts has seemingly created even more. However, none of the present disputes, whether long-standing or more recent, has assumed such proportions as to provoke serious inter-state tensions.

Maritime disputes in the Caribbean

| Parties concerned | Object / nature of litigation | Character and present status of the dispute |

| Belize and Guatemala | Terrestrial and maritime | Several disputes over lap... Guatemala is demanding nearly half of the territory of Belize to the South of the River Sibun, as well as the ‘cayes' of Sapodilla and Ranguana which it controls. These terrestrial disputes impact on the delimitation respectively of territorial waters and EEZs. Guatemala is also involved because to date its access to the sea is closed by the territorial waters of both Belize and Honduras. The negotiations held in 2002 under the auspices of the Organization of American States (OAS) proposed the creation of an international maritime corridor. It was generally accepted that the principle needed to be confirmed by referendum. But the latter has not been submitted to the vote in either of the two countries. |

| Belize and Honduras | Terrestrial | Honduras lays claim to the ‘cayes' of Sapodilla to the detriment of Belize. Any solution will depend on the resolution of the territorial and maritime disputes between Belize and Guatemala (see above). |

| Guatemala and Honduras | Maritime | Belize and Honduras propose the sharing of a maritime corridor with Guatemala in terms of the accord negotiated under the auspices of the OAS. Guatemala rejects the demands put forward by Honduras regarding Sapodilla and Ranguana, currently administered by Belize. |

| Colombia and Honduras | Maritime | Several islands remain in dispute. An accord has attributed the sandbank of Serranilla to Colombia, but it claimed equally by Jamaica, Nicaragua and the United States, as well as including Bajo Nuevo. Nicaragua disputes this accord and opposes the demands of Colombia in respect of the waters East of 82° W (see below on Colombia and Nicaragua). |

| Colombia and Nicaragua | Maritime and terrestrial (archipelago of San Andres) | Nicaragua disputes Colombia's sovereignty claim over the archipelago of San Andres and Providencia – Albuquerque, as well as over several other rocks and sandbanks (see below). A 1928 Treaty hat established Colombia's rights over the waters and islands to the East of 82° W, but during the Sandinista period, Nicaragua denounced this Treaty, claiming that it had been signed under pressure during the American occupation. In 1988, the Nicaraguan government reiterated its in principle demands whilst accepting Colombian occupation. |

| Colombia and Nicaragua-Honduras- Jamaica-USA | Maritime | Lined up against Colombia are the concurrent claims by Nicaragua but also by Honduras and Jamaica to the distant rocky islets of Santa Catalina and the sandbanks of Banco Rocador, Banco Quito Sueno, Banco Serrana, Alicia, Serranilla and Bajo Nuevo. The United States in turn also reserves the right to claim some of these islands. |

| Colombia and Panama | Maritime (islands of the Caribbean coast) | Panama maintains its claims to certain small-coasted islands, arguing that they had been re-attached when it was as province of Colombia (up to 1903). It considers that these historic rights should over-ride any mechanical ruling based simply on equidistance. |

| Colombia and Venezuela | Maritime and terrestrial | Colombia has not abandoned its claims to the islands. Los Monjes, at the entrance to the Gulf of Venezuela, and occupied by Venezuela during the 1950s, was subsequently attributed to this state by the 1980 bi-lateral accord. The steps to agree on accord on the maritime boundary of the islands, and the tracing of a line closing the bay failed. The whole affair has given rise to periodic tensions, sometimes violent, as well as to detente between the two neighbours who are not short of more important issues to concern them. |

| United States and Haiti-Cuba-Jamaica | Terrestrial and maritime (Island of Navassa) | Haiti, supported by Cuba, claims sovereignty over the island of Navassa, currently occupied and administered by the United States. The linked and final delimitation of the maritime boundaries of Cuba-Jamaica and Cuba-Haiti remains in abeyance. |

| Cuba and the United States |

Terrestrial (Guantanamo) |

Cuba disputes the presence on its territory of the enclave of Guantanamo: 118 km2 rented at 3 300 US dollars per annum (not encashed since the missile crisis of 1962). In terms of the accord, which runs until 2033, the US alone will decide whether or not to hand back this enclave. |

| Venezuela and Dominica-Saint Vincent-Saint Lucia-Saint Kitts &Nevis-Antigua & Barbuda | Maritime and terrestrial (Aves islands) | These different states do not accept that the Aves be considered as island territories giving the right to an EEZ and an extension of the continental shelf in favour of Venezuela, arguing rather that they are merely isolated rocky islets and not true islands. The interpretation in effect restricts their own respective potential EEZ claims. They also dispute Venezuela's sovereignty over these islets, and the treaties signed with France, Netherlands and USA confirming the transfer. |

| Guyana and Suriname | Maritime and terrestrial | A boundary dispute results from disagreement over which upstream river (Cutari or Corantijn) constitutes the primary watercourse. On the latter hinges Suriname's claim to the Cutari Delta to the South of Guyana. This historic dispute was revived after the independence of Suriname in 1975. As a consequence, oil prospection became impossible: in 2000, Suriname coastguards arrested a vessel from Guyana found prospecting in the contested zone. |

| Guyana and Venezuela | Terrestrial and maritime | This dispute stems above all from the land boundary. Venezuela contends that the course of the River Essequibo forms the natural boundary with Guyana and reflects the Schomburgk line of 1848, later imposed by the United Kingdom as the international boundary in 1886. US arbitration in 1899 allowed for some reciprocal concessions, and the drawing of the new line in 1905. In 1970, Venezuela signed a moratorium with the UK and independent Guyana, but refuses now to renew it, thereby periodically reactivating this dispute and, in turn, preventing the delimitation of the maritime boundary, putting on hold any oil prospecting. |

| Haiti and Jamaica | Maritime | The claims of Haiti in respect of the Island of Navassa, administered by the USA, prevent the establishment of a maritime boundary at the meeting points between Cuba-Haiti and Cuba-Jamaica. |

| Honduras and Jamaica | Terrestrial | The two parties both claims Bajo Nuevo and Serranilla, also claimed by Colombia, Nicaragua and the USA. |

| Nicaragua and Honduras-Colombia | Maritime | In 1886, Honduras and Colombia signed a treaty, which established their maritime boundary as a simple extension of the terrestrial limit along the 82° meridian. Nicaragua denounced this treaty as well as the “Honduras Act on Maritime Zones,” and disputes the installing of Honduran troops on South Cayo. It takes the case to the International Court of Justice in 1999 for a delimitation of the boundary between the three states concerned. The ICJ decides in favour of Honduras. |

| Jamaica and Nicaragua | Maritime | Negotiations are suspended on the resolution of disputes relating to the islet of Bajo Nuevo and the Serranilla Sandbank, claimed equally by Colombia, Honduras and the USA, as well as to those of islands claimed by Nicaragua and occupied by Colombia. |

| Suriname and French Guiana | Maritime | The discussion in question relate to the limits of territorial waters and of the continental shelf. |

| Antigua & Barbuda and Saint Barthélemy (France) | Maritime | Dispute relates to the delimitation of the maritime boundary. |

| Saint Martin (France) and Sint Maarten (Netherland Antilles) | Terrestrial and maritime | The issue of the end point of the terrestrial boundary which determines the limit of the territorial waters is still in abeyance. |

1 Energy generated by exploiting the temperature variations between surface and deep waters.

2 Christian Fleury (op. cit.).

3 Chapter 8, article 21… but not signed by Venezuela, and not ratified by Colombia.

4 Carta Etnografica de Mexico (1864); Islas Mexicanas (1946) published by the Ministry of Education.

5 Fishing grounds in question were discovered by Martinique fishermen at the same time as the battle of Diên Biên Phu (1954).

top

|

|