- Agriculture (2006-2009)

- Agriculture : mutation (2005-2006) FR ES

- Agriculture: emblematic landscapes

- Agriculture: food-self sufficiency (2005-2007)

- Agriculture: production (2007-2008)

- Commerce extérieur (2001) FR

- Currencies

- Economic organisations (2009)

- Fishing (1995)

- GNP per capita (1995)

- Integrated energy strategy (2004-2007)

- La Chine dans la Caraïbe FR

- La pêche dans le bassin Caraïbe - 2019 FR

- Le bassin caribéen, théâtre affirmé d'une guerre d'influence sino-étasunienne ? FR

- Nouveau contexte pétrolier (2015) FR

- Nouvelles donnes régionales (2004-2006) FR

- Sugar and Oil (1999-2011)

- Tax havens (2007-2010)

- Tax havens (2008-2012)

Fifty years have passed since the first steps were taken towards some form of integration, albeit initially limited to Commonwealth states, and the commonly accepted idea today of a ‘Greater Caribbean.' This long march has seen both clearer definition emerging in terms of the conception and representation of Caribbean region, and confirmation of the necessary cooperative structures of integration.

An increasingly accepted representation of the region

For the Caribbean and those working towards its integration, the first difficulty to be surmounted was its regional representation. The latter, which goes beyond the single question of image, determines the way in which one thinks, projects and organises any approach. In fact, the representation of Caribbean space has long been punctuated by indecision, as the following most commonly used images serve to illustrate in their different ways:

- The image of an arc or string of beads (of islands) which appears to give emphasis to juxtaposition, physically constrained solidarity, but which is also drawn out, stretched. Here, the only frontiers are those of beginning and end, those of the extremities.

- The composite images, “binary” in type, already establishing the differences between “Greater” and “Lesser” Antilles, or between those islands “Windward” and those “Leeward,” which focus more on internal sub-division than on the region's external boundaries.

- Lastly, the image of the basin itself often used to define the “Greater Caribbean,” whose American shores offer support to the notion of a ‘spatial unit,' and perhaps even a shared destiny. Such images in their complexity may be used as much to describe a projected incorporation (the “American lake” of the revised Monroe Doctrine) as to justify part of a regional typology (American or Tropical ‘Mediterranean').

No image, however, calls into question the diversity of the Caribbean, that mosaic of languages and cultures inherited from colonisation that diversity of institutional arrangements (independent states, associated states, dependencies (of the Netherlands, France, and Great Britain), and finally those disparities in levels of development, resources and territory. Paradoxically, without doubt, this diversity has provided the motor for the process of integration over the last forty years. Today (2009), the notion of a ‘Greater Caribbean' (‘Gran Caribe' / ‘Grande Caraïbe') is widely used as much by the Association of Caribbean States (ACS) as by the Caribbean Community (CARICOM).

A slow but constructive evolution towards integration

It is difficult to establish a precise starting point for the process that in 1958 concluded with the creation of the Federation of the West Indies (FWI), and in 1972 with CARICOM. In truth, the road to federation had already become, albeit partially a preoccupation of the British Crown in the 19th century. Grenada, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent are already administered by the Windward Island Federation from 1833 to 1958. A similar organisation the Leeward Islands Federation administers the islands of Anguilla and Barbuda, Dominica,1 Montserrat, Saint Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla. At the same time, from 1932 onwards leaders like the Grenadian Theophilus Albert Marryshow, recognized today as one of the founding fathers of the FWI was arguing for a federation dotted with a certain degree of autonomy. In 1947, the projected federation was agreed by the leaders of the Labour Party assembled in Jamaica, with in principle acceptance by Great Britain, already fully occupied by various troubles across her colonial empire. Negotiations opened in 1953. They ended in 1958 with the creation of the Federation of the West Indies between ten countries of the British Commonwealth: Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, St. Vincent & Grenadines, Grenada, St. Lucia, Dominica, Antigua & Barbuda, St. Kitts & Nevis, Montserrat, and Jamaica.2

Following the independence in 1953 of the two large British islands (Jamaica and Trinidad), the Federation was dissolved and moves toward creating a common market of the Caribbean was launched. The project would be realised in two stages: firstly, the establishment of CARIFTA (Caribbean Free Trade Association) during the period 1965-1972, and subsequently its replacement by CARICOM in 1972 after the Chaguaramas Conference in Trinidad. These 25 years (1947 to 1972) would prove decisive in the construction of a Caribbean project. In effect, an active core represented by the Anglophone islands in search of some degree of integration has demonstrated the viability of such a project, and established the basis of an opening to non-Commonwealth member states.3 This enlargement would be one of the major achievements of the 20th century for the Caribbean.

Enlargement, growing, and deepening levels of cooperation

From 1972 onwards, the process of integration would simultaneously evolve in two directions: enlargement and deepening ties. The Chaguaramas Treaty of the 4th July, 19734 in reality, embraced two accords

- An accord establishing the Caribbean Community;

- Another setting up the Caribbean Common Market and creating the instruments of economic integration (external tariffs, common fiscal and investment policies).

Several characteristics warrant further comments. From the outset, the ‘Community' is conceived as “open” without exclusivity. Accordingly, articles 3 & 2 of the Treaty anticipate that “Membership of the Community shall be open to any other State of the Caribbean Region that is in the opinion of the Conference able and willing to exercise the rights and assume the obligations of membership.” Furthermore, those countries adhering to the Chaguaramas Treaty are not obliged to sign up to both accords. This is the position adopted by Bermuda, which participates in community activities without being involved in commercial exchanges. In short, the integration alluded to in the signed Chaguaramas Treaty is above all, notwithstanding the economic agenda, a community project involving populations whose well-being is both the central subject and end-product of cooperation in areas as varied as they are important (health, culture, human rights…).5

The experiences of European integration, the proximity of the USA, ‘Anglo-Saxon' pragmatism are very much further factors that will help shape the singularity of Caribbean integration. Pragmatism reveals itself in any assessment of the development disparities between countries of the Caribbean. Firstly, it should be noted that the two largest islands of the former West Indies Federation (Jamaica and Trinidad & Tobago) represent 60% of the population and 50% of the national domestic product of CARICOM. Integration had to take into account the particular circumstances of the LDC (Least Developing Country) in relation to the MDC (Most Developed Countries). From 1966, the small states of the Caribbean attempt to re-organise themselves so as to increase their negotiating position within the larger community.6 A new stage is reached with the signing of the Treaty of Basseterre (capital of St. Kitts and Nevis), on 19th June 1981, establishing the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS). The OECS remit was to ensure greater awareness of the specific development problems of very small states, by means of assistance and access to specific policies (relating to external representations, management of a common currency – the EC dollar –, by the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank, as well as development advice from the Eastern Caribbean States Export Development Agency (ECSEDA).

One year after the creation of the OECS, as if to underline the active US engagement previously alluded to, Ronald Reagan in May 1982 launches the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI) which, one approved by Congress, in 1983, becomes the Caribbean Bain Economic Recovery Act (CBEREA). Destined to engage all 24 countries of the Caribbean Basin with the exception of Cuba, Nicaragua, Puerto Rico and Colombia, the CBI was above all introduced to do-away with customs duties on Caribbean produce entering the USA. Geopolitically, the CBI may be considered as a US counter-offensive to the mooted Caribbean integration project (including Central America) and at the same time, a subtle operation indirectly favouring the penetration of American imports and investment into the region.

Echoing the US initiative, Canada proposes a similar accord to 26 Caribbean countries designed to favour exchanges between Canada and the CARICOM member states. This becomes CARIBCAN (Caribbean-Canada Trade Agreement) announced in February 1986, and like the CBI operating on the basis of preferential customs tariffs relating to the Canadian market for produce from those countries of the Commonwealth-Caribbean.

The opening up of the market anticipated by articles 3 & 2 of the Chaguaramas Treaty would largely take effect in the 1990s. The latter initially build on a spirit of coordination in relations with other regional organizations, i.e. the CARIFORUM created in October 1992, regrouping the independent states of the Caribbean, signatories to the Lomé Convention linking the ACP to the European Union. The declared objective is the coordination of European aid and related adjustments regarding the interest of countries in the region. The Dominican Republic is thus linked to CARIFORUM through the free trade accord signed with CARICOM in 2001. The years following the creation of CARIFORUM would see a proliferation of free trade accords with Venezuela (1992), the Dominican Republic (1998), and of cooperation with the ACS (1997), and Argentina (1997). Not to be left behind, the CARICOM would multiply its external links towards Japan, Spain, Chile, and South Africa (1999); as well as accords with other states and third party organisations.7

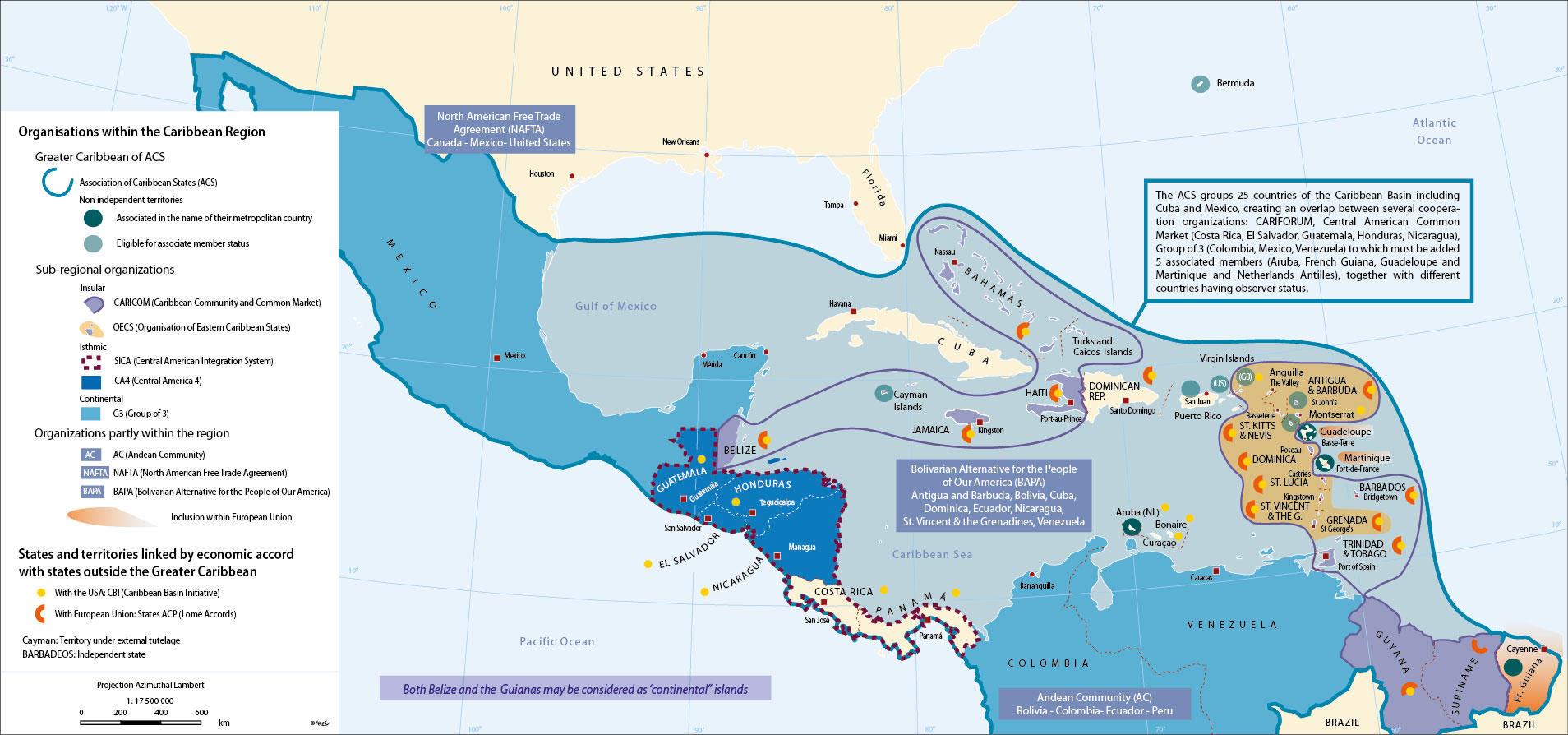

The major event of the decade would be the signing on the 24th July 1994 in Cartagena, Colombia, of the treaty leading to the creation of the Association of Caribbean States (ACS), now indisputably the largest grouping of states in the Caribbean. The ACS brought together 25 states of the region, including Cuba and Mexico, which in turn allowed inter-linkage and cooperation between several existing organisations, such as CARIFORUM, the Central American Common Market (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua), the Group of Three (G3: Colombia, Mexico, Venezuela) to which should be added the five associate members (Aruba, France – representing French Guiana, Guadeloupe, and Martinique – and the Dutch Indies), in addition to various countries with observer status. The ACS has set itself the objective of developing concerted intergovernmental action, working towards the establishment and promotion of the Greater Caribbean, a region of exchange and collaboration in the domains of commercial, financial, cultural, scientific, political, and technological development.

The Single Market and the Caribbean Community

On the 5th July 2001, a new stage is reached in the already long history of Caribbean integration meeting in Nassau in the Bahamas for the 22nd Convention of Heads of State, the attending representatives decide on a revision of the Chaguaramas Treaty, and the creation of a single market and economy for CARICOM (Caribbean Single Market and Economy - CSME). The first accords for its establishment are signed in January 2005 by Barbados, Belize, Jamaica, Guyana, Suriname, and Trinidad & Tobago to take effect on the 1st January 2006. The revision of the Treaty foresees amongst other changes relating to the 9 protocols, the creation of a Caribbean Court of Justice, the introduction of a community passport8 designed as much to facilitate intra Caribbean movement as to develop a sense of common identity. Further actions are envisaged such as the merging of the region's airway companies, monetary union, a common civil society charter...

What then, in the light of such initiatives, does the future hold for Caribbean integration?

The recognition given today to the existence of a ‘Greater Caribbean' is no longer questioned. The mechanisms in place in respect of different domain of activity allow member states to engage with their particular areas of interest in furthering the construction of a Caribbean community. The decades to come will inevitably offer challenges to be overcome in the context of increasing globalisation, the desire of the single market to dictate all decisions affecting the activities of the basin, the very real dissensions amongst member countries in respect of sovereign and national interest on the one hand, and the desire nonetheless to fully engage in a community-wide project on the other.

Economically, the Caribbean Common Market will not have met all expectations, given that community relations remain weak and be-dwelled by the inadequate inter-island transport links within the Caribbean basin. Again relations with other majors economic communities like the European Union,9 or the Free Trade Area of the Americas operate in a context made difficult by the injunctions of the WTO (particularly with regard to banana exports).

Politically, Caribbean integration did not opt to follow the path of supra-nationality, as in the case of its European precursor. Up until the present, the parliaments of the member states have voted for numerous projects and decisions promulgated by the Conference of Governments Leaders. It may not always be thus and the next step seem to be in preparation as much the role assumed by the Legal Affairs Committee (LAC), working on the harmonization of legislations between member states, as in the desire to engage more fully their own populations (as a prelude to a next step in democratic representation?).10

As for the particular role of the American French Departments (AFD) – Martinique and Guadeloupe – first and foremost, it has to be viewed in terms of the acceptance of both Caribbean reality and identity. Lines of communication, whether by air or sea, do not help. Reconcile such a concurrence, beyond which their integration is subject to very precise and clear regulation by the decentralised governance granted to regional executive bodies. The integration of the AFD territories brings into relief regulatory statutes relating to both cultural identity and “franco-french” institutional question. Imbricated within this complex tautology, also lied challenges that need to be confronted.

Half a century on, marked globally by the aftermath of the Second World War, accession to independence of the European colonies and the effects of the ‘Cold War,' regional cooperation in the Greater Caribbean at the start of the 21st century now requires further progress on a number of fronts: raising awareness of the huge environmental challenge, in itself requiring significant action at both local and regional scales; freeing up transport links in order to facilitate easier movement of both people and goods; reinforcing a communal sense of Caribbean identity in the public imagination so as to open the way to new forms of voluntary associations, a Caribbean basin which has the advantage for many decades of not experiencing the destructiveness of armed conflict found in other parts of the world. A precious advantage indeed, deserving to be exploited further.

Association of Caribbean States (situation as of 30.12.2007)

| Independent Member States | Associated States, territories as yet not independent | Founding observer organisations | Observer States |

|

Antigua and Barbuda Bahamas Barbados Belize Colombia Costa Rica Cuba Dominica Dominican Republic El Salvador Grenada Guatemala Guyana Haiti Honduras Jamaica Mexico Nicaragua Panama St. Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia St. Vincent and the Grenadines Suriname Trinidad and Tobago Venezuela |

Aruba (overseas territory of the Netherlands) French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Barthélemy et Saint Martin (overseas territories of France) Dutch Antilles (in process of dissolution since July 2007 to be replaced by Sint Maarten, et Curacao) Netherlands on behalf other Dutch islands; eventual adhesion to ACS not yet decided |

CARICOM - 1996 SELA (Latin American Economic System) - 1996 SIECA (Secretariat for Central American Economic Integration) - 1996 SICA (Central American Integration System) - 1996 UNECLAC (United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) - 2000 CTO (Caribbean Tourism Organization) - 2001 |

Argentina Brazil Canada Chile Egypt Ecuador Finland Great Britain India Italia Korea Morocco Netherlands Peru Russia Spain Turkey Ukraine |

Organisations promoting integration of Greater Caribbean

| State | Geographical Region | Caribbean organisation | Continental organisation | |||||

| ACS | CARICOM | OECS | FTAA | OAS | Rio Group | |||

| 1 | Antigua & Barbuda | Lesser Antilles | Associate member 1974 | |||||

| 2 | Anguilla | Lesser Antilles | Associate member 1999 | Associate member | ||||

| 3 | Aruba | Lesser Antilles | Associate member (Netherlands) | |||||

| 4 | Barbados | Lesser Antilles | Associate member 1973 | |||||

| 5 | Bonaire | Lesser Antilles | Associate member (Netherlands) | |||||

| 6 | Curacao | Lesser Antilles | Associate member (Netherlands) | |||||

| 7 | Dominica | Lesser Antilles | Associate member 1974 | |||||

| 8 | Grenada | Lesser Antilles | Associate member 1974 | |||||

| 9 | Guadeloupe | Lesser Antilles | Associate member (France) | |||||

| 10 | Martinique | Lesser Antilles | Associate member (France) | |||||

| 11 | Montserrat | Lesser Antilles | Associate member 1974 | |||||

| 12 | St. Kitts & Nevis | Lesser Antilles | Associate member 1974 | |||||

| 13 | St. Vincent & the Grenadines | Lesser Antilles | Associate member 1974 | |||||

| 14 | St. Lucia | Lesser Antilles | Associate member 1974 | |||||

| 15 | Trinidad & Tobago | Lesser Antilles | Associate member 1973 | |||||

| 16 | Bermuda | Greater Antilles | Associate member 2003 | |||||

| 17 | Cuba (4) | Greater Antilles | ||||||

| 18 | Dominican Republic | Greater Antilles | ||||||

| 19 | Haiti | Greater Antilles | Associate member 2002 | |||||

| 20 | Cayman Islands | Greater Antilles | Associate member 2002 | |||||

| 21 | British Virgin Islands | Greater Antilles | Associate member 1991 | Associate member | ||||

| 22 | Jamaica | Greater Antilles | Associate member 1973 | |||||

| 23 | Puerto Rico | Greater Antilles | ||||||

| 24 | Bahamas | Greater Antilles | Associate member 1983 | |||||

| 25 | Turks & Caicos | Greater Antilles | Associate member 1991 | |||||

| 26 | Colombia (3) | South America | ||||||

| 27 | Guyana | South America | Associate member 1973 | |||||

| 28 | French Guiana | South America | Associate member (France) | |||||

| 29 | Suriname | South America | Associate member 1995 | |||||

| 30 | Venezuela (2) | South America | ||||||

| 31 | Belize | Central America | Associate member 1974 | |||||

| 32 | Costa Rica | Central America | ||||||

| 33 | El Salvador | Central America | ||||||

| 34 | Guatemala | Central America | ||||||

| 35 | Honduras | Central America | ||||||

| 36 | Mexico (1) | Central America | ||||||

| 37 | Nicaragua | Central America | ||||||

| 38 | Panama | Central America | ||||||

CARIBCAN: Preferential accord between Canada and Anguilla, Antigua & Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Bermuda, Belize, Virgin Islands, Costa Rica, Dominica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Montserrat, Netherlands Antilles, Nicaragua, Panama, St. Kitts & Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent & the Grenadines, Trinidad & Tobago, and Turks & Caicos. Dating from June 1968, with the aim of facilitating commercial exchanges, assistance, development, and industrial cooperation between Canada and countries of the Caribbean Commonwealth.

1 Attached in 1939 to the Federation of the Windward Islands.

2 Two countries, British Honduras (Belize) and Britain Guyana (Guyana) refused to join the FWI.

3 Eric Williams, then Price Minister of Trinidad and Tobago, spoke in 1962 of the necessity of enlarging cooperation to include the Dutch and French islands, including the three Guyanas.

4 The Treaty would be revised in 2001 in Belize, leading to the creation of the Caribbean Single Market of economy (CSME).

5 The involvement of civil society would be in February 2002 the object of the “Liliendaal Declaration” affirming that “civil society has a vital role to play in the elaboration of regional and social policies.”

6 The West Indies Associated State Council (WISA) was created in November 1966 by Anguilla & Barbuda, Dominica, St. Lucia, Grenada, and St. Kitts & Nevis; later joined in 1969 by St. Vincent & the Grenadines.

7 Preferential accords with Venezuela in 1993 and Colombia in 1995. Free trade accords with Cuba in July 2000, the Dominican Republic in December 2001, and Costa Rica in March 2004. Negotiations are in train with Canada, European Union, and MERCOSUR. Note that 12 of the 15 members of CARICOM (with the exception à Barbados and Trinidad & Tobago) form part of the Petrocaribe Alliance dating from 2005 with Venezuela, allowing those signatories to purchase oil from the latter state at preferential rates.

8 On the 7th January 2005, Suriname became the first member state to issue a (Caribbean) community passport; joined in April 2005 by St. Vincent and Grenada, and St. Kitts & Nevis on 25th October. The remaining member states would follow suit as and when their stocks of old passports ran out.

9 The French deputy Christiane Taubira, born in French Guiana, was asked by the President of the Republic to research ways of establishing Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA) between the European Union and the African, Caribbean, and Pacific Group of States (ACP). Emphasis would be placed on projects sustaining the dynamism of existing regional integration policies. Also to be addressed were the ways in which France overseas territories could derive maximum benefit from these new economic and commercial initiatives.

10 Refer on this subject to the report of the Commonwealth Foundation “Maximizing Civil Society Contribution to Democracy and Development: Report from the Caribbean Consultation“ - June 2003.

top

|

|